It’s Oscar time! Yeah, tonight’s the night when the Academy push whatever agenda is at the top of their list whilst making sure to either deny awards to actors who’ve already received one (Sean Penn) or present them to directors who didn’t necessarily make the best film, but have been long overdue for one (Martin Scorsese). Of course, their agenda can often override these principles, so much so that even Tom Hanks can get an Oscar for playing a gay part!

And who can forget Michael Moore’s infamous 2002 Oscar acceptance speech in which he talked about American violence both domestic and abroad? It was considered so controversial at the time. How dare he draw parallels between the international perception of Americans and their tendency for violence due to being home to a massive armed underclass! Clearly, he was a few years too early, because it’s now pretty much accepted that the world reputation of the United States has been needing a little improvement (hence Barack Obama’s election victory).

Many hopes are hanging on Barack Obama, just as they were on Bill Clinton and Tony Blair in the 90s (and, yeah, we know what happened there). Back then, I was a student writing as co-editor for the college magazine under the guidance of our brilliant media teacher Becky Parry, who even garnered us some local media attention – but, whilst congratulating me on an editorial piece on the recently deceased Lady Di, didn’t understand my choice of two other subjects: animal rights, and professional wrestling.

Mickey Rourke may very well receive a (deserved) Oscar for Best Actor at tonight’s Academy Awards for his performance in The Wrestler, portraying past-his-prime professional wrestler Randy “The Ram” Robinson, and demonstrating the art form of soap opera stuntwork and storytelling through simulated violence. And that’s the crux: far from the real-life hazards of barbaric boxing (which Rourke’s also participated in), pro wrestling is a kind of theatre that reflects the attitudes of America today, and whilst without the presence of a union and thus rendering many retired wrestlers broke and broken-down, it at least affords them the opportunity to pick and choose how intense and painful their performances are to be in the name of entertainment.

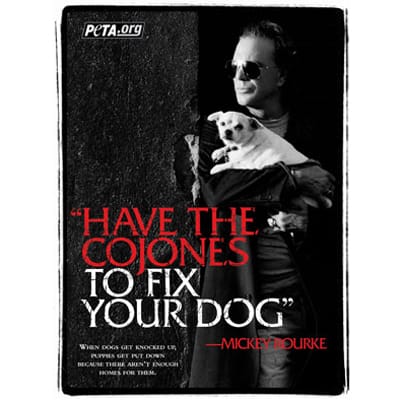

No surprise, then, that one of PETA’s recent campaigns features Mickey Rourke himself holding his precious pooch in an attempt to raise awareness about “animal birth control.” So, years after my choice of subjects for the college magazine, it’s also now becoming accepted that, far from being a circus, pro wrestling is not inherently in direct opposition to peaceful lifestyles or even animal rights. It does, however, require a little more work when it comes to the treatment of the humans involved.

In the film Brassed Off, about coal miners fighting for their unionised livelihoods in Northern England, Pete Postlethwaite, portraying colliery brass band leader Danny, states “I thought that music mattered. But does it bollocks! Not compared to how people matter,” adding that “the point is – if this lot were seals or whales, you’d all be up in bloody arms. But they’re not, are they? No, no they’re not. They’re just ordinary common-or-garden honest, decent human beings. And not one of them with an ounce of bloody hope left. Oh aye, they can knock out a bloody good tune. But what the f*** does that matter?”

And that’s what’s strange about the world we live in. When we see a violent act committed on masses of people – usually in the name of “foreign policy” – we rarely react as emotionally as we do when we see beached whales, or seals clubbed, or birds covered in oil after a tanker disaster, or even a news story of pet neglect. Even in movies, we react differently to a human being killed than we do to an animal being killed.

Animal rights are important, of course, but human rights are the priority, and they’re completely connected anyway: it’s no coincidence that animal abuse rose in South Yorkshire after the strongly-unionised coal pits had been closed in such a draconian way, weakening the British unions and decimating entire communities. When workers lose their rights, it’s a loss of human rights as well, and when that happens, humans get desperate; they start to abuse drugs, spouses, children, and animals, as well.

The unionised industries that built communities and provided us with essential resources can’t be compared to the retail-driven, low-paid, short-term, part-time, temporary jobs that replaced them, peddling rubbish wanted but not needed, driving people into debt to make ends meet, surrounded by advertising – thus the “economic crisis.” There needs to be a true value of human rights, but we can’t even begin to do that until we value workers.

– Jay Baker; Doncaster, England