Our childhoods have a hell of a lot to answer for, don’t they?

Whether it be playing with dolls in kindergarten as my mother dismissed “concerns” from other parents, or going to school with a She-Ra action figure and combing her hair and provoking bullying that would contribute to the reasons my mother pulled me from school and taught me at home herself when I was 11, or even just being referred to as “little girl” by some who lived several streets away and didn’t really know me, there are many examples of gender norms being an issue for me as a youngster. It had been a veritable neighbourhood news event when I took my action figures to spend the day with my friend Katherine and her dolls, and we played with said toys interchangeably; it just wasn’t done, apparently. Indeed, it only happened once. It probably wasn’t worth the hassle.

In a predominantly coal mining town where our working class home was literally split apart by the subsidence from coal mines underneath our house, with the 1980s miners’ strikes in full swing, my siblings and I enjoyed a liberal home life where the prejudices of Thatcherite Britain were rejected and instead rastafarians and camp thespians were welcomed into our collapsing semi-detached house in danger of becoming fully detached by structural damage!

My mother had always worked various industrial jobs (where she’d almost always agitate if there was no union), but when I came along as the third of three children, and my dad was in steady employment operating fork lift trucks at the nearby glass factory, my mother dropped to just one job that she’d been doing anyway – that of “housewife.” This at least enabled her the opportunity to teach me at home herself, which – I can reveal, decades later – generally consisted of asking me what I wanted to learn on that day, sometimes involving a visit to a museum or nature reserve, with the occasional brushing up on books from the standard education system. Visiting relatives asked what the heck was wrong with me, because I had my head in a book rather than getting into mischief like other boys in the family who were told were “proper lads!” I was developing a really bad feeling about all of these gender expectations.

Perhaps not coincidentally at this time away from schoolyards and instead in my backyard where I was using my imagination as a superhero, or alien, or animal, I slowly stopped kicking a ball around and eventually completely lost interest in my dad’s favourite sport of association football, becoming intrigued instead by American football, and – when we were able to afford satellite television – American professional wrestling, featuring an array of even more camp characters, heroics, histrionics, and muscular melodrama from the likes of Mr Perfect, The Genius, “Ravishing” Rick Rude, Brutus “The Barber” Beefcake, “Million Dollar Man” Ted DiBiase, “Sensational” Sherri, “Macho Man” Randy Savage and Miss Elizabeth, to name a few who grabbed and retained my attention immediately. A year later I attended a live show, and bought a t-shirt featuring the main star, the Ultimate Warrior.

As I watched the pro wrestling programmes on TV, I probably enjoyed relatives pointing out the pre-determined nature of the show about as much as, say, anyone enjoys sitting in the cinema and being constantly reminded that the movie they’re watching is all pretend, as if my teenage mind didn’t know it was obviously rigged and largely simulated – but that’s what I found comforting and reassuring about this “violence”: my hero might repeatedly punch the villain in their face then drop them right on their head in the ring before defeating them to a chorus of cheers, but the villain would be back the next week without an injury, or even a bruise, rather than being seriously injured or killed…and that was just fine by me. Men in my family felt quite the opposite about the matter: the fact the violence was simulated but exhibited not as a movie but as a sporting event – complete with ring and referees – really offended them and what seemed to be a masculine demand for legitimate bloodshed, the most masculine of them all going from on the verge of fisticuffs with each other one minute, to the next minute totally united in their aggressive ridicule of my geeky bespectacled self watching his “fake” wrestling and writing fan-fiction of it, rather than the traditionally “masculine” sports culture offerings.

The women in my family were different, of course, and supportive – and going from playing with dolls to watching simulated violence featuring over-the-top flamboyant characters was wholly accepted by them, and I was essentially their mascot, draped in glitter or happily having my nails painted; my family noticed I was much the same as when I was preferring to hang around with girls at school and bullied by the boys for it, and I was constantly reminded it was just fine if I turned out to be gay. But I didn’t. Even if I had wanted to, the looming threat of violent reaction from men in my upbringing was too intimidating to consider, because it was seemingly fine for other people’s families but would not be acceptable in ours. Then there was the rampant homophobia in my town called “the AIDS capital of the country”…

I’ve also written before about how my adulthood saw me lose my way. In the early 1990s I attended nightschool to attempt to gather qualifications, and again my friends were housewives and single mothers, but as I moved to day classes (basically: college) I grew up, filled out, and my “outsider” vibes and nerdy coiffed hair styled after some of my favourite comic book characters were interpreted as simply a “Rebel Without a Cause” 1950s throwback, and attracted friendship from fellow students for the first time in nearly a decade. Though I took abuse from some for my clean-living, plant-based, straight-edge lifestyle, I was still quite liked by others for my “individualism” a la Sailor from Wild at Heart, and after years of tabloid sensationalism and misinformation about AIDS, and being in the “AIDS capital of the world,” much like Sailor himself I took part in homophobic language and gay-bashing narratives with others, which confused my family (and probably only piqued their suspicions of me being in the closet – while simplistically assuming my interest in female bodybuilders was because I was attracted to “masculine” people, only to be reminded that I was equally fascinated by drag queens at the time…which was perhaps in turn only used as further evidence!) Ultimately, it just wasn’t that black-and-white, as I’ll explain.

All through my time outside of school, probably my best friend in the whole world (who for years would happily wrestle me and even “kick out” on a two count!) was a part-Old English Sheepdog who my family had adopted after being found abandoned for being a “mongrel.” When I was 19, she became gravely ill, and ironically enough I began dating a woman who, eleven years older than me, worked as a veterinarian and gave me her professional opinion on our options for my dog. But more than that, her scientific mind, and her maturity, set me right on many things, not least the myth that AIDS was a disease that only affected gay people – and that blew my mind, and stopped me in my tracks. Why would people hate someone for something that doesn’t even hurt anyone? I didn’t understand, and in the future I tried to resist false narratives and homophobic dialogues more, but failed to stand up anywhere near as much as I ought to have, and being true to yourself is a political act few of us are brave enough to do. It’s not enough to just throw out your Ultimate Warrior t-shirt because you find out the man’s a raging homophobe.

A college video I created featured the Halloween-esque theme tune of one of my favourite pro wrestlers, Goldust, who garnered absolutely nuclear heat with fans and opponents alike simply for his androgynous character; I never revealed to my tutor where I’d acquired the music from, but still received a good grade as far as I recall – I actually remember sneaking the CD into the editing suite, yet I’m not sure what I was hiding more: potentially violating copyright laws, the track being a pro wrestler’s entrance music, or the wrestler in question being Goldust. I was already continuing to take my fair share of abuse at college, and much of the homophobic undertones were by now being turned and directed towards me during classes. Every Wednesday evening I’d seek my refuge meeting a group of friends for months on end, all of whom happened to be female, and who later admitted, “We loved you being in our little gang, but just assumed you were gay.” In addition, the fact that teenage years of poor skin complexion led me to continue wearing some form of foundation makeup for the rest of my life, or that I constantly shaved off bodyhair, and my love for Ed Wood didn’t all exactly combine to deter classroom digs that I was a secret crossdresser (which eventually I’d just end up embracing wholeheartedly). College was starting to feel a lot like school, and I was wondering if I’d ever be able to peacefully exist within these kinds of environments.

In returning for another year at college, I took inspiration from the performance personas of different pro wrestlers in order to put on a brave face, particularly the Kurt Cobain-inspired stars Raven and especially Brian Pillman, who wore waistcoats over James Dean t-shirts and carried a walking cane – and I literally copied these absurdities. Yet it worked. It deterred antagonists I sought to keep at bay, and (as I’ve mentioned here before), had an unexpected side-effect of gaining me more friends, especially those of a quirkier mindset. Having been compared to James Dean in amongst the constant “Fifties Throwback” jibes previously, I figured I needed to learn more about him and the post-war rebellion against the suburban nuclear family with its patriarchal bullshit and reinforcement of societal expectations.

My own suburban nuclear family life was at this time becoming fraught with my own identity issues, exacerbated by revelations about where I possibly really came from (something I have never and at this stage will never discuss publicly out of respect for those who raised me), and ironically I’d go on to resent customs and traditions based on “blood family,” which – as time passed and my political education progressed – I found far too similar to supremacist politics. I also hated the expected norms of graduating, getting a 9-to-5 job, driving a car, buying a house, and having a wife and two kids. Part of this, if I’m honest, was probably because I knew I couldn’t cut the mustard even if I actually tried to pull off that kind of life.

I’d always accepted that my prospects in life were going to be limited, given that my home education made me resistant to structures and systems I hadn’t forged for myself – never mind the exams and qualifications, or lack thereof – and I had it in my mind that if by early adulthood I was going to end up in a box, be it cardboard or even a wooden one six feet under, I might as well try and make the most of things while I could and – as James Dean believed – “experience everything.” So I started drinking, tried a few different drugs over the years, showed up to events in full drag –– finally co-opting those Ed Wood comparisons –– and had all kinds of sexual experiences with all kinds of people, both women and, yes, men (the latter encounters enlightening me on just why risk of STDs was more likely when these hide from bigotry, remain secretive, and are therefore more likely casual and fleeting…yes, it soon made sense to me: my hometown’s status of “the AIDS capital of the world” being a self-fulfilling prophecy with all of its ignorant homophobic abuse driving people into the shadows). My mind was opened and I lived with more freedom – if unbeknownst to some people in my life. When I became besotted with a trans woman I’d spent a night with, men in my life reacted to the news with various forms of masculine coping mechanisms – it was seen as either a funny, perverted, sexual conquest, or as something to be completely denied as having ever even happened. Meanwhile, she didn’t want to keep seeing me because she wanted a guy who was more masculine, one who was less sensitive and enjoyed soccer and beer and fighting. I was failing to play my gender role right across the board for so many people! However, this also had some advantages.

I had close, sometimes intimate, relationships with trans men, who I proudly considered my friends at many times in my life – a real pattern – in part, it seemed, due to that very fact that I wasn’t a typical toxically masculine cisgender man. Meanwhile, cisgender heterosexual men often randomly declared they didn’t want to be friends with me anymore, usually coming back apologetically, only to then suddenly end the friendship again, citing my politics or personality as a problem, one having fooled around with me one drunken night after watching WrestleMania (!), and another saying he’d spent years “worshipping” me in “a weird hetero-homo kind of way” (whatever the fuck that means!) and relished telling me just how many people had laughed in ridicule when he made a point of telling them I still wrote pro wrestling fan-fiction. Ultimately, my failures to fully play the part of the “lad” was an issue; for example, my telling other guys to ease up on misogynistic behaviour either pissed off my closest friends or inspired them to join me in calling it out, later actually blaming me for them losing macho friends because of it. Some chalked up my fishnet clothing, black eyeliner and nail polish to being a punk rocker; others said I was “trying too hard” to be different. I was just doing what I felt comfortable with, the same way they wanted to wear a suit and tie to work, or a polo shirt and shorts to relax, or whatever. Too often, just being me was cited as an affront to the cishet men in my life; I’d done nothing to them, they admitted; they just resented me, even if they couldn’t explain why.

But hey, that’s not to say that all the women in my life were understanding of my sexuality, and some I’d been seeing simply struggled to put it into a nice neat little box. A few cautiously asked if I was deep in the closet, some screamed homophobic slurs at me in arguments, others even physically abused me, enjoying the fact I never hit back, never mind barely defended myself (after all this, another partner taunted and goaded me, calling me a “little bitch” and then promptly called the cops when I finally cracked and, regrettably, pushed her away from me – but that’s another story for another time). The assumptions around my sexuality and my gender seemed like a trap at every turn; if I was passive, sensitive, or admitted to sexual encounters with anyone other than a cisgender woman, I was apparently in a closet and/or not masculine enough, and yet as soon as I stood up for myself, I had to be punished because they expected better from me and held me to higher standards than the “usual” man in the cishet role. (Thankfully, not all women I dated were like this, and eventually I’d settle down with someone who found that all this made perfect sense, and accepts me for it to this day, even supporting me in writing this here now. Who knew that it’d be the pro wrestler we’d both end up considering one of our favourites – Kenny Omega – who’d also become such an LGBTQ+ icon with his ambiguous Golden Lovers storyline?)

One of the pro wrestlers I’d really liked from the independent circuit was Veda Scott, who I had chance to see live when my partner got us tickets to a local “Queen of the Ring” one-night women’s wrestling tournament a few years ago. I had to contain my excitement as she stood on the ropes right in front of us because I got the vibe she was playing the heel, and I wouldn’t be helping the show by cheering the villain. In retrospect, hell, I could’ve just shamelessly made a fool of myself and “marked out” for “Veda Time.”

I always rooted for, and in many ways preferred, women’s wrestling – right back from the days of Madusa, Bull Nakano and Aja Kong. Joanie Laurer, known as “Chyna,” emerged as a breakthrough pro wrestling star, and I spent later years defending one of my main interests to family members on a whole other level: “She looks like a man” was countered by my point that “She’s a woman, therefore a woman looks like she does.” While I had started to believe sexuality was some sort of spectrum for many of us, I was by this time beginning to also realise that gender was a construct. It was a similar story when my attempts to develop a relationship with my dad included my interests having to return to soccer, where he and I would attend both Doncaster Rovers and Doncaster Rovers Belles games. Having preferred encouraging girls to play the sport in the playground as a schoolkid, and as an adult playing co-ed soccer while living in Canada and creating something I called Solidarity Soccer (anti-capitalists of all genders playing semi-competitive casual games in the park), it was perhaps only a matter of time until I became involved in the sport in a way that aimed to challenge toxic masculinity, and back in Britain I co-founded a women’s football club, AFC Unity, with my partner Jane Watkinson, where I’d constantly battle against the patriarchal traditions of the Football Association – including its outdated rules around gender, eventually fighting alongside others, and raising funds, to turn the UK version of Solidarity Soccer into a safe space for trans and nonbinary folks, sadly just as the pandemic hit.

Even in my coaching experiences, if I wasn’t facing the hostility of opposition managers encroaching and occupying space, I was constantly told by some players themselves that I wasn’t directional enough, or authoritative enough, or ebrasive enough, until I stood up against bullying in the team, then the bullies called me dictatorial for ousting them, proceeding to join teams where managers operated like drill sergeants, and were accepted for it. Toxic masculinity, I realised, transcends – it permeates cultures, it seizes and occupies ground, and is accepted, emulated, even replicated; wrapped up in aggression, tribalism, and nationalism – association football has been a breeding ground for it for many years, and its governing institutions are built on capitalist foundations.

I’ve been proud to have been on the board of E.D.E.N. Film Productions, whose incredible community projects have empowered people from the LGBTQ+ community to vocalise their own stories and exhibit them to inspire viewers, including me. It has had an immense impact on me and made me reflect on my own “story,” for lack of a better term. One of my favourite authors, Douglas Coupland, believes we all often desire to live, or at least perceive, our lives as stories.

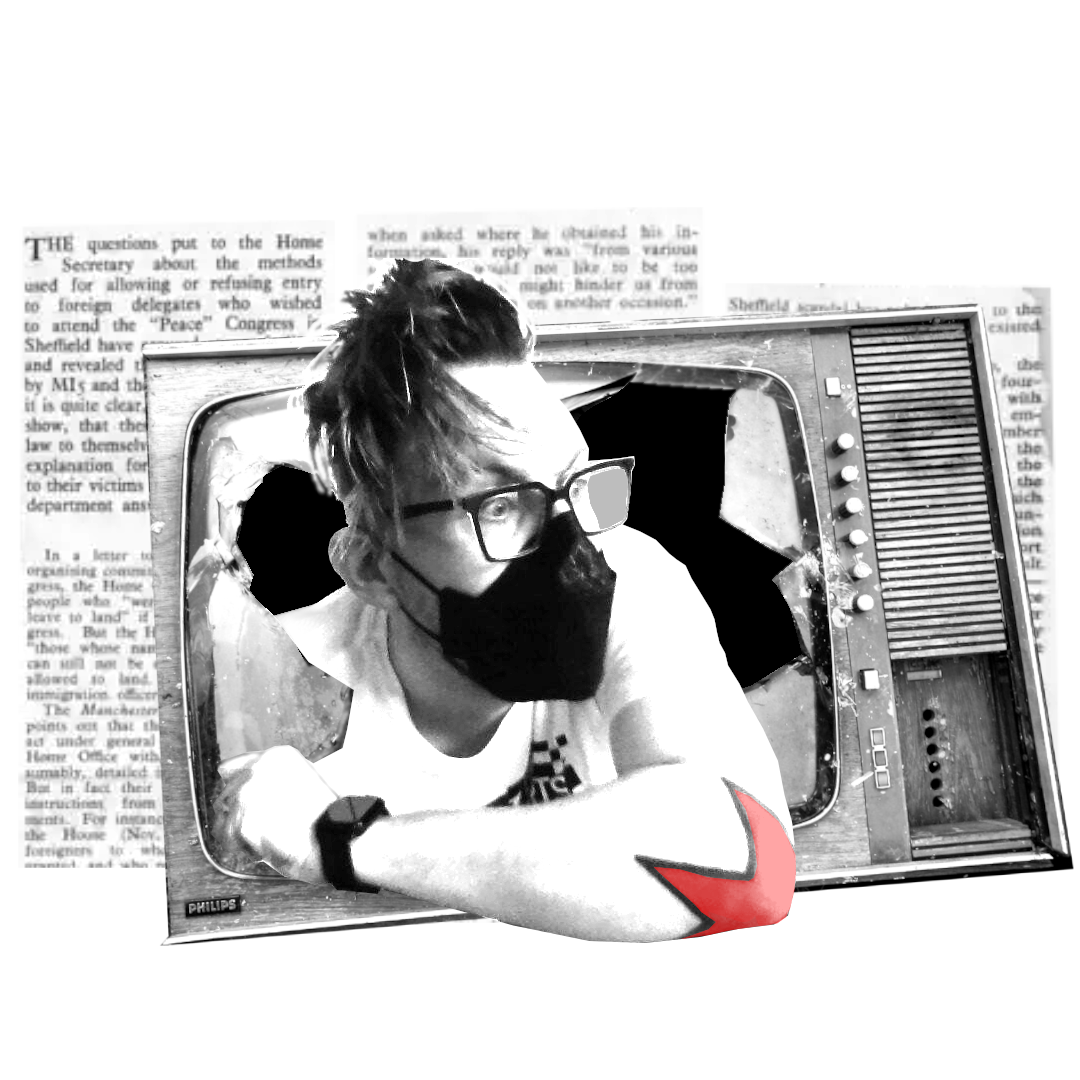

Throughout my adult life, I’d enjoyed the privileged position of being seen as a white cisgender man who had several lucky breaks I wouldn’t have enjoyed without that status. I’ve been afforded opportunities in education and work and if I’m honest I’ve played up that part of me to keep those doors opening, only for it to be slammed back in my face when the toxic masculine men who enjoy positions of power realise I’m not really one of them, after all – and I’m resented for it. In fairness, I was misleading them. Despite being omnisexual, for years I’ve only ever revealed that when I’ve been asked about it, and largely been considered an ally of the LGBTQ+ community. Yet the idea that Jay Baker is a typical man is misleading – “he” is not, and I can’t just be “him.” I’ve spent the last few years resisting embracing “they” and “them” as pronouns because even though some in the LGBTQ+ community are entirely supportive of it, I was concerned those that didn’t know me well wouldn’t understand the context and see it as performative activism at best and, at worst, a co-opting of something important. But I cannot honestly say applying just “he” or “him” to me tells the true story of who I am, or at least the whole story. In recent years I’ve been proactive on finding my way back to who I feel I am at my core, who I was before societal norms and expectations messed with me. As a youth and community worker, I can’t tell young people to stay true to themselves if I don’t adhere to who I am.

I realised this, and had inspirational examples along the way.

I realise it’s Pride month, and while many capitalist organisations who perpetuate the hierarchies that capitalism depends upon co-opt Pride for profits, there have been so many more brave and inspirational statements and stories and I feel that if I were to continue to keep quiet about my own experiences or my own identity, I could be part of the problem rather than the solution. So here I am. My name is Jay Baker: he/him, or they/them. I’m fine with either. But definitely not just one. That isn’t me.

Edit: Veda Scott themselves acknowledged this post!