Bio

Who the hell do I think I am? I'll try to explain.

If my brief bio on the Fediverse wasn't enough for you then welcome: you've come to the right place to know more about me and my background.

What can I say? The personal is political, so I cover a lot of these events through anecdotes within the posts here on this site. I’ve been told I’ve successfully managed to avoid self-aggrandisement, which I’d say is somewhat inevitable since I'm not a clout-chaser (and have little to brag about, right?)! The purpose of this page is merely for you to have more of an idea about who I am. So here goes. To that end, I’ll try and start at the beginning. Time to rewind.

Born at 332 ppm, I came into the world the same year that Johnny Cash gave us “psychobilly” while punk itself exploded onto the scene to uphold the ethos of “D.I.Y.” as VHS (and home taping) also arrived. Sure enough, I was raised to adhere to the punk principle of “do no harm, take no shit,” particularly instilled in me at the age of eleven when I was pulled from an abusive school environment, and — while the man I believed to be my dad worked longer shifts at the nearby factory — I was taught at home by my mother, who battled education authorities in order to do so. I kept that man’s surname, but changed my forenames to be gender-neutral, and became a vegetarian (and later vegan), supported in all these decisions by my mother, who by the time I reached my teenage years, marched right beside me on my first political demonstration.

The future scared me; I was unable to even really envision one. My plan was to grow up and just avoid being in a box: cardboard, concrete, wooden, or metaphorical, I suppose. That would be an achievement, I figured.

Spending most of my formative years being educated by a working class woman helped form my intersectional feminism, despite living in Conservative Britain in the 1980s, with marginalised Black and queer folks all frequent friends visiting us in the unlikely refuge of our semi-detached house that was split down the middle — no, literally split down the middle from our neighbours, due to the subsidence underneath from the now-closed coal mines deep underground. Those roots ran deep too, since both of my grandfathers relied upon that industry for work before it was targeted by Margaret Thatcher for daring to be strongly unionised.

Beyond the propaganda around the miners' strikes, the TV was another box I'd grown to resent, viewing with suspicion its set “programming” built around the traditional capitalist 9-to-5 daily routine I knew I wanted no part of, resembling school far too much for my liking, with its authority figures requiring people to be good little cogs in the machine generating profits for the capitalist class through work and consumption; TV commercials peppering the programming. The only illuminating broadcasts to catch my interest in the background of my largely nocturnal life of reading, writing, and drawing, were European cinema, obscure shows, late-night classic films, and Laurie Pike's quirky overview of Manhattan Cable — the principle of public-access television in particular fascinated me — but once I left home, I'd never willingly watch the boob tube again; never again own a set rigged up to receive channels; never again pay for a license.

Love at First Site

Ah, the Internet. Truth be told, I fell in love with it from the moment I first logged on after booking that corner computer in the library of Doncaster College, where my mother had “accidentally” enrolled me with the wrong date of birth, in truth so I could pursue qualifications sooner than the system would usually accept me, as she assumed I was ready to be let loose upon a world beyond my existence of home-taping collections, magazines, fan fiction, drawings, cassette players, comic books, fifties sci-fi, and professional wrestling.

As I went through my teenage years, the aforementioned kitschy culture provided the main reference point for my choice of clothing and overall style, with long coats and loud shirts, even bolo ties and walking canes, topped off with a quiff hairstyle, leading my fellow students to assume I was some sort of retro rockabilly throwback, and a careers advisor giddily mocking my appearance while telling me I'd certainly never work in the media, just maybe McDonald's; when I rejected that by simply stating I loathe meat, he ridiculed me for that, too, citing teeth!, lions!, deserted islands!, and other unashamedly ignorant nonsense. Other needling took place throughout my college experience, quickly becoming a little too much like school for me, and I experienced a growing concern that I was destined to always feel oppressed in such institutions many around me seemed to consider “normal,” if not acceptable. So, after the initial frustration, followed by proper reflection, I decided I wasn't capable of ever changing who I was at my core, and doubled-down, standing my ground more and standing up for myself with even greater expressive flamboyance — unexpectedly and quite remarkably gaining friends for it, but also even more enemies: I would be assaulted several times, the injuries sustained from one attack so severe that some remain to this day.

I was barely able to exist in formalised further education and into higher education, scraping by with supporting statements from Doncaster College media tutors who apparently felt I did actually possess a worthwhile, fairly unique understanding of their subject, leading me to being accepted onto a three-year media degree at Barnsley College, which included a trip to Paris, where I met some French-speaking Canadians who insisted I visit them in Canada sometime. I did, and met an animal print-adorned American in Toronto, who invited me to stay with her — indefinitely. Still struggling with hierarchical formal learning environments (and abusive, authoritarian tutors), I dropped out of my degree with just a few months left in order to blow what was left of my student loans and escape to the States.

When I somewhat inevitably returned to the UK with my tail between my legs, I signed onto the “dole” and was put on Tony Blair’s welfare-to-work programme, working weekdays for social security payments for most of the year before being hired to work for Rotherham Council as a youth and community worker in the multimedia department. When funding for that was terminated, I set up my own non-profit called SilenceBreaker Films, bringing in my fellow media degree drop-outs to work on it with me where possible, and engaging disadvantaged young people from post-industrial communities devastated by Thatcherism, and with Blair’s New Labour failing to reverse the country’s neoliberal trajectory.

I attended the historic February 15th, 2003 march in London protesting Blair’s invasion of Iraq alongside over a million more of my fellow protesters, and, maintaining my love affair with the web, continued to document much of the movement for Indymedia while attending meetings and actions around anti-war activism and opposition to oppression linked to such wars: imperialism, colonialism, racism, and of course capitalism itself. It was on this scene that people first introduced me as a “media activist,” the first time I’d ever even heard the term.

I went on to interview the likes of Kate Wilson, Prem Sikka, Teresa Hayter, Peter Tatchell, Shami Chakrabarti, Richard Murphy, Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, in addition to numerous campaigners, academics, and activists. Even though I was probably only vaguely “leftist” or socialist, still very much finding my way politically – and my documentary work was mostly aimed at the average British tabloid reader – I’d remained one of the few anti-establishment documentarians making purely independent films largely from their own pocket, and was branded a “public enemy” by fascist websites such as Redwatch. Nonetheless, I continued capturing content for Indymedia in my spare time, in addition to running SilenceBreaker Films. However, both of those endeavours would fail, in different ways.

Film Feed Failed

With the boom-and-bust nature of self-employment, I went from months of rent arrears one moment, to booking overseas flights the next. I never considered the future, as long as I was avoiding boxes.

I kept going back to Canada, meeting with media activist infoshops from GlobalAware in Toronto to Adbusters in Vancouver, and made connections in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) in particular, where I ended up shacking up in a housing co-operative with someone who shared my passion for communication studies, often taking care of her kids while she pursued the subject at Wilfrid Laurier University, whose students urged me onto the board of Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group (LSPIRG). I was asked to give a speech for a journalism conference, where I met filmmaker Tim Knight, who stayed in contact with me and – when I asked him about the emergence of citizen journalism – cited his fellow Torontonian, the 60 Minutes correspondent Morley Safer: “I would trust a citizen journalist as much as I would trust a citizen surgeon.” I later made the counterpoint that if the modern equivalent of professional journalism is professional health care where the doctors are killing people instead of saving them, then you’d take your chances with someone else having a go at it. And that was where I believed we were at with journalism. I wanted to turn SilenceBreaker Films into SilenceBreaker Media, inspired by the radical artists and activists I’d met who were using not just film but also print, graffiti, street theatre, still photography, hacking, and much more to raise awareness of important issues.

I continued my guerrilla documentary activities in the GTA, and also took part in union drives, demonstrations, direct actions, and made speeches at rallies and radical events in ways which were probably not smart for someone on a temporary visa I was merely repeatedly renewing only by leaving and re-entering the country. At the same time, I was trying to continue hiring friends and keep funding coming in for SilenceBreaker Films over in Britain, only able to access grants for its community workshops by having a committee in place, who, while I was in Canada, cynically ousted me and wound it up, apparently transferring its assets to their friends, while blaming the collapse of the organisation, even to funding bodies, solely, squarely, and entirely on myself – as a committee, exercising their rights but accepting no responsibility. I have remained individually blackballed by some of those funding bodies ever since.

Meanwhile, Indymedia was experiencing the opposite issue: this global network’s non-hierarchical structure was both its strength and its greatest vulnerability, as this extended to a lack of editorial oversight, and Indymedia became overwhelmed by conspiracy theorists and anti-Semites, largely collapsing in on itself around the world as its more responsible guerrilla reporters mostly aimed their energies elsewhere. Others pursued paid careers in an “alternative” media buoyed by pages on emerging social sites such as Facebook and Twitter, where profiles were created and raised by self-proclaimed pundits; Oxbridge types like Owen Jones connecting with me online until they gained more clout and I was no longer useful, and where meanwhile I neglected to promote myself or my skills, and I quickly returned to poverty, experiencing periods of homelessness, though fortunate to avoid rooflessness by the kindness of comrades offering their basements, floors, couches, and even spare rooms – lessons in solidarity, not charity. Nonetheless, I wasn’t yet ready to fully comprehend such lessons.

Leggo My Eggo

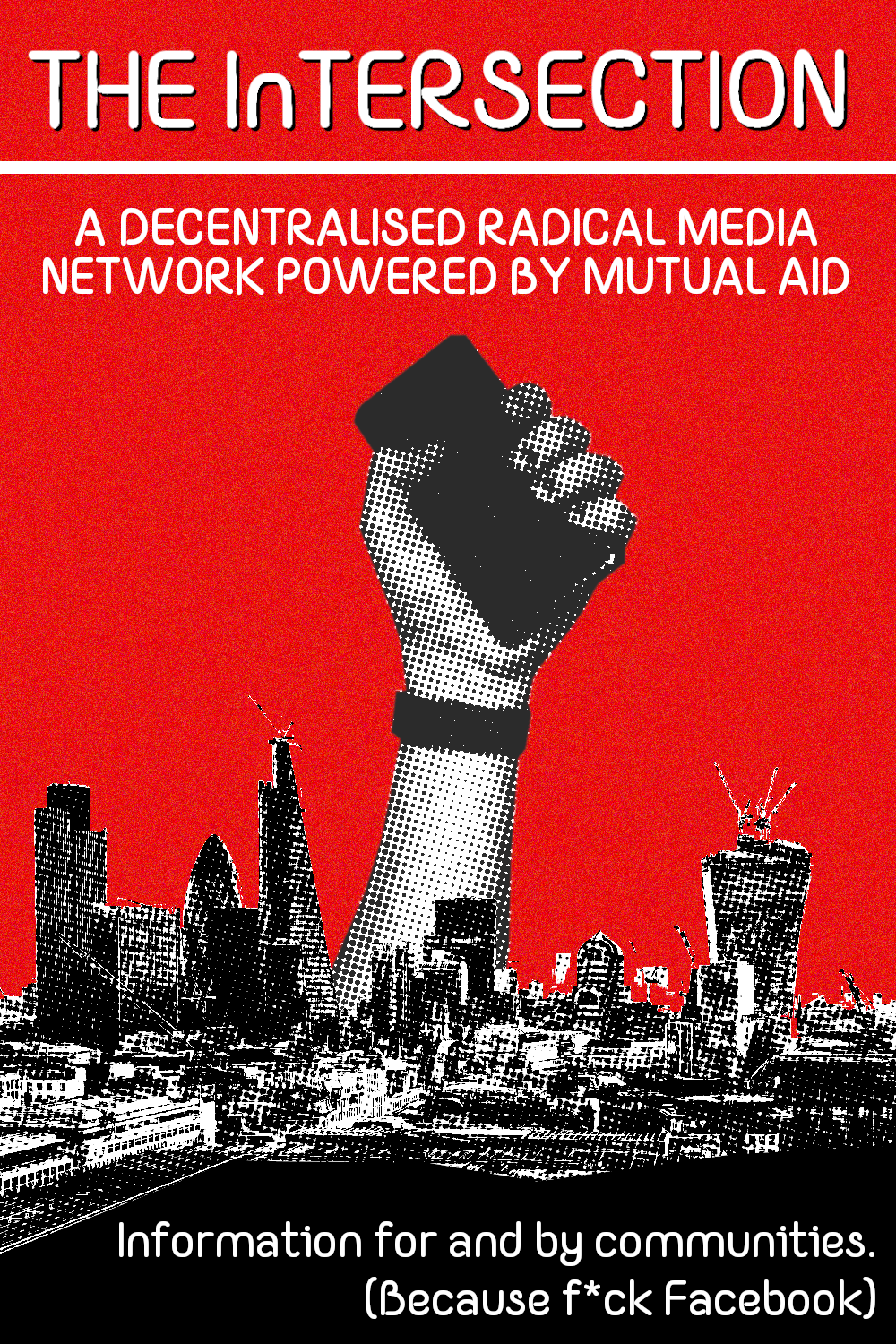

As a result of those couple of examples of abject failure, with an irrational fear of being burnt again, and unable to let go of such insecurities (or ego), I foolishly doubled-down – steadfastly setting up SilenceBreaker Media, which I’d conceived while still in Canada, to be multi-discipline and broader in scope, yet also more locked down legally as a non-profit limited company in the UK, again with a board but also with me initially included as a (managing) director, as well. I was now, apparently, a "social entrepreneur." Attempting to become more financially but also socially and environmentally sustainable, we focused on reconditioning computers, installed with Linux, to help get people online and making their own multimedia, under the slogan “connect, communicate, change.” We even devised – and piloted – a social network alternative to Facebook called "The Intersection."

Bruce Hanlin, lecturer in journalism and media at the University of Huddersfield, invited me to deliver a talk to his students because, he told me, “Your ‘alternative’ and varied way into the media might look more realistic at a time when the established media are in retreat and job opportunities at a virtual standstill.” In the talk, aside from speaking about the SilenceBreaker Media concept, I touched on topics such as journalistic integrity in an era of elitism in journalism, and how the BBC’s cloak of “impartiality” protects it in suppressing voices of dissent – after all, as the late Desmond Tutu said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” But importantly, it was interesting to me that, for this talk, I was seen as part of the “alternative” media, but very telling that Hanlin also used the term “established” media. Because there is hardly anything “mainstream” about a media that is owned by, operated by, and propagandises for, the establishment.

Therefore, there was another talk I gave – when formally launching SilenceBreaker Media as a brand-new Fellow of the School for Social Entrepreneurs – where my speech had to follow that of a suited representative of one of the School’s corporate sponsors, who rather liberally confessed that communities don’t need things “doing to them” by corporations but instead need support. So I went up and, unable to stop myself, spontaneously stated that corporations needed things “doing to them” by communities, “and I’ll leave it to your imagination what those things might be.” Despite laughter from the majority of the audience, the suit in question looked unimpressed, and afterwards the managers of the School seemed to be displeased with me, too – possibly because as part of my actual “graduation” speech, rather than use ambitious business language about SilenceBreaker Media, I instead focused on claiming overtly aggressive anti-establishment media was needed, offering two tales from the areas around my birthplace to illustrate my point: the BBC’s manipulation of footage that falsely portrayed striking coal miners in a negative light in 1985, and The Sun’s coverage of the Hillsborough disaster that told lies about Liverpool FC fans, 97 of whom died. Both of these examples of deliberately misleading media narratives by industry “professionals” demonstrated acts of propaganda for authoritarian force. Noam Chomsky once stated that “Propaganda is to a democracy what the bludgeon is to a totalitarian state.” With The Sun newspaper essentially banned from the city of Liverpool and readership in decline nationally, trust in the BBC decreased as well. And justifiably so. But that vacuum hadn’t been reliably filled. Though it wasn’t about to be filled by SilenceBreaker Media.

My attempt to propel SilenceBreaker Media forward as a social enterprise meant I was suddenly regularly engaged in meetings with not just those corporate suits but also entrepreneurs, city councillors, and MPs who unwittingly gave me the ultimate lesson in my political education, as I witnessed supposed “socialists” actively and aggressively undermine, scupper, sabotage and even smear laughably mild social democratic alternatives, thus condemning populations desperate for answers to find few available for them in the traditional politics that already brought them to the brink. In addition, when Covid-19 hit, the “left” utterly failed to effectively emphasise the importance of ongoing mutual aid and COVID-safe workplaces, instead following along with state policy of capitalism over care; commentators and clout-chasing leftists falling over one another to race back to “normality” in an ongoing pandemic – a mass disabling event. Subsequently, conspiracy theories and right-wing authoritarians promising order increased their appeal, and were able to further their ideology of ableism and eugenics. Fascism is on the rise, all around the world – even as art, activism, and anarchism rise up to face the challenge. Welcome to what my friend The Artist D aptly refers to as “The Roaring Twenties.”

Wake Up Call

Those creeping threats are real. While some parents have been resisting the “indoctrination” of the school system by teaching fascism to their children at home, my mother had taught me anti-fascism, having removed me from school because of its abuses of power from teachers and headteachers in the hierarchical education system, not just bullying from classmates. The problem was power itself, I came to realise: whoever you vote for, the state always wins - and my aversion to boxes has since extended to ballot boxes, too.

The education I was given outside the state system highlighted a D.I.Y. punk ethos: my mother was herself figuring out how to effectively teach me, while in turn I was having to figure things out for myself without any peers, pupils, or classmates, as it were. We worked with whatever appealed to me in order for me to learn: watching educational films; reading well-written books and magazines about topics I was interested in to better grasp the English language; using collectible items to understand mathematical concepts; embarking on local nature trails; visiting museums and galleries. This D.I.Y. punk ethos is what I applied to my guerrilla journalism and documentaries, which, like a non-fiction Orson Welles (or, more likely, Ed Wood), I researched, wrote, produced and directed, with extra crew hired from grants, crowdfunding, and even my own pocket, so disconnected from capitalist realities that I even let the cinemas exhibiting my films keep all the box office takings after screening costs were covered, clearly confusing a lack of revenue or proceeds with “non-profit” principles. No one can reject capitalistic culture on their own. Despite the D.I.Y. principle, punk was always about cooperation over competition. It means “do it yourself,” not “do it by yourself.” Media needs to be driven not by an individual, but as a collective effort; not through hierarchy, but through horizontalism – not just as part of co-operatives, but as part of mutual aid. Every time we envision how our communities would be served beyond the capitalist economic system, we still always include media as an important part of the society we want. And it's wrong to suggest important things can only exist if they're monetised. That old dream of “The Intersection” can still be realised, but on these terms; with these principles.

I for one have never been content with existing in a capitalist world; it has been a struggle, in every sense. And, as I’ve explained in my Manifesto here on this site, media must be people-powered by citizen journalism in order to truly combat capitalism. The Fediverse offers us some opportunity to achieve this, and reminds many of us why we first fell in love with the Internet to begin with.

“Breaking the silence” isn't about being a “voice for the voiceless” because, as Arundhati Roy stated: “There's really no such thing as 'the voiceless.' There are only the deliberately silenced, or the preferably unheard.”

Today, in addition to working on developing The Intersection, I continue to work in communications, consultation, and community facilitation, mostly in the area of digital media and technology for non-profits, and am a member of Open Rights Group and the IWWFJU. Recently, as acting secretary, I helped to revitalise the IWW branch for my sub-region and am part of Acorn renters union, as a tenant in social housing - where I largely work from home while caring for my partner (who was disabled by Covid) full-time. As the pandemic continues, I’m also proudly involved with Sheffield Mask Bloc and am part of a radical communal care collective, passionate about the principle of mutual aid.

I'm a bit of an old film buff, and in addition to my enthusiasm for documentaries I grew up being inspired by French New Wave cinema and German Expressionism, and for my sins have been a big Burtonverse Batman nerd since I was a kid, but am probably redeemed by my love for The Doom Patrol, X-Men '97, and The Boys, and when I’m not reading comic books or getting a kick out of professional wrestling (which is still more real than borders or nations!), I can probably be found playing around with technology or feeding the local crows. I also enjoy hand-sewing very badly, and cooking less badly, often while listening to my music, podcasts, or The Indie Beat Radio.

So far managing to dodge boxes (at time of writing), and still trying to “do no harm, take no shit,” sticking to such principles has cost me many connections and opportunities for income over the years, so suffice to say I welcome work offers, especially for worthwhile causes. You can also show your support by subscribing to this site, recommending it to others, commissioning me to write for your publication, inviting me on your podcast, or dropping a donation.

For enquiries, email me or contact me on Mastodon and elsewhere on the Fediverse. (I hold no accounts with Facebook/Meta, Twitter/X, Google, Microsoft, and the like – if you see an account on such sites claiming to be me, it’s either not me or an unused profile...so hey, feel free to let me know either way!)