Read part one here.

When Warners’ Batman brand was ready for reboot in 2005, things looked relatively promising: director Christopher Nolan was no slouch, and seemed to take the source material seriously enough, while he also brought in a host of skilled actors – Morgan Freeman, Rutger Hauer, Tom Wilkinson, Cillian Murphy, Gary Oldman, Liam Neeson, Michael Caine, and Christian Bale, of American Psycho fame, a wise choice for the dual role of both Bruce Wayne and Batman. Both Nolan and Bale instantly went on record during hype, paying respectful homage to Tim Burton’s vision but then claiming they’d be more true to the source material.

At just over two hours long, Batman Begins did what it said on the packaging: it spent most of its efforts telling the story of how an orphaned rich kid grew up to turn to vigilantism utilising his wealth of resources. It was a well-devised journey that showed him training in the East while on his travels, before returning to Gotham City to defeat his demons and adopt the mantle of the Bat. It even started on intelligent terrain, focusing on his development from vengeful, arrogant killer to recognising his power and responsibility to root out the causes of disadvantage in Gotham’s streets.

Having said that, there were significant departures from the spirit of the Batman stories along the way. Of course, the argument is always that Batman is adapted to various interpretations, but some of Nolan’s changes – unlike Tim Burton’s previous update of the Penguin character, for example – lent nothing, just diluted.

Despite the bragging about staying true to the Batman stories, while audiences were shocked by Burton’s Batman revealing Bruce Wayne’s alter ego to his girlfriend Vicky Vale, already in Batman Begins, Batman’s true identity was essentially known to not one, but three other different people (Rachel Dawes, as well as, arguably, Lucius Fox, and, of course, Ra’s Al Ghul). But the failure to back up their boasts didn’t just lie there…

Bale’s Batman didn’t have a gravelly whisper; it was a growl, at times comical to even the staunchest of Batman Begins fans, and his eyes were small, mouth often gaping as he tried to convey emotion through the mask. And while Bale’s Bruce Wayne was deliberately obnoxious, rather than reclusive, to cover for his secret identity (and that sure is another perfectly acceptable take on the character to an extent), what it sacrifices is a warmth and vulnerability, even in his lone moments, that he really needs to have in order for audiences to sympathise with the privileged protagonist. This is not a major complaint, but is important, because it reflects what the franchise would become.

Alfred, meanwhile, was not a traditional butler from an upper-class background, but, here, a chirpy cockney chappie cracking jokes, which suggests the part was written specifically for Michael Caine, who created his own backstory to the character to suit himself, showing no signs of the proclaimed universal loyalty to the source material. The excellent Gary Oldman is here sadly more reminiscent of Ned Flanders than any traditional imagining of Jim Gordon, but at least a credible effort offering the character more depth and respect than previous versions. And while Lucius Fox, Carmine Falcone, and, to a lesser extent, Ra’s Al Ghul, were all done justice, the same can not be said of Dr Jonathan Crane and his alter ego the Scarecrow, barely fleshed-out, barely seen, and reduced to ridicule by the time he’s seen carried around on a horse at the film’s climax – Cillian Murphy, and the character, deserved better. In the comics, the Scarecrow is a manifestation of Jonathan Crane’s desire to use fear as an equaliser after he was bullied by brutes as a child for his lanky, nerdy appearance; here, he was just a mad doctor garnering little sympathy.

Finally, Gotham City – and the entire approach to design, including the grotesque “Tumbler” Batmobile – was based on Nolan’s premise that the film be as urban and gritty as possible, meaning that what was blatantly Chicago in several shots was presented as Gotham, a city so-called because of its dark gothic nature…but not so here. Nolan apparently wanted his crew to think of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner during production, but Batman Begins lacked Scott’s political intelligence in addition to his creativity; you’re hard pushed to find a single breathtakingly beautiful shot anywhere in the film, let alone anything approaching gothic and oppressively twisted. The approach means the film is more likely to date badly, which is presumably just fine with the filmmakers. The movie’s visual ugliness reflects its lack of heart, and that was something apparent when it was over – it felt more like Nolan had an idea for a movie with clever twists, and just transplanted the Batman brand onto it so it would be marketable. Two of Hollywood’s finest composers, James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer, combined to score the film yet Batman’s “theme” always felt like a build-up without a crescendo, and the score was never going to be any match for Danny Elfman’s. But all in all, this was, of course, an improvement on the Joel Schumacher versions…though who would anybody be able to brag to about that? Making over $370 million, Nolan couldn’t match Burton’s 1989 debut, but certainly satisfied Warners enough for them to finance further films.

In addition to drawing inspiration from Blade Runner, to his credit Nolan also drew from some DC Comics source material such as Batman: Year One by Frank Miller, a decent starting point from which to have Batman begin, but again also a very dark place in terms of spirit rather than visuals (Burton, as has been mentioned, focused on the reverse: dark style, with well-meaning content).

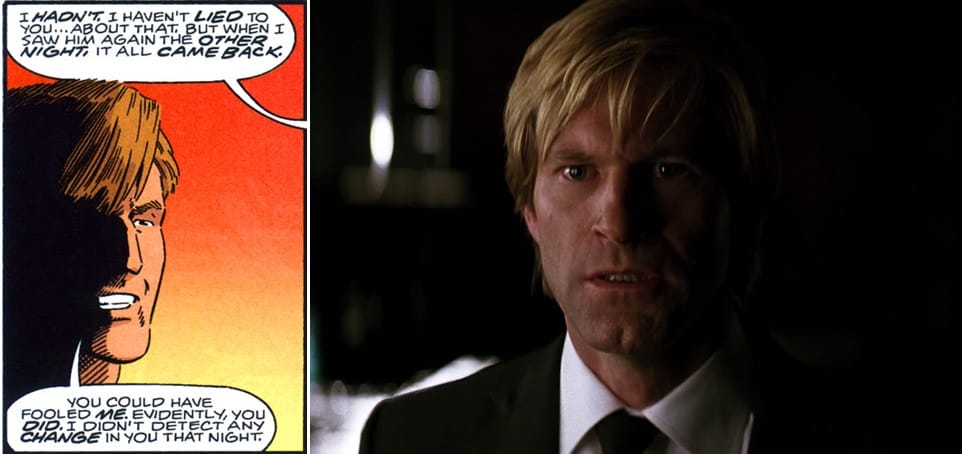

It was from this dark place that Nolan built his over-long, slightly pretentious sequels, The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises, both of which brought back Scarecrow – or, rather, Jonathan Crane – for brief scenes in which he was worthless. But other characters were wasted, as well – such as that of Two-Face, a villain who was failed by Schumacher and, here, was failed by Nolan. It would surely take an entire film to do justice to the fascinating, deep, dark, coin-flipping antagonist as he was in Batman: The Animated Series, and yet here he was an add-on, half his face ravaged by acid so much so that, through Nolan’s CGI, it looked absurdly zombiefied, bones and tendons galore, all while Nolan excused the rest of his removal of Batman comics details in the name of – yes – “realism.” And let’s not forget Steve Englehart, Batman comics writer who penned the Dark Detective stories where Batman’s former girlfriend is seeing a handsome, blonde, upright politician scarred and lured into the dark side by Harvey “Two-Face” Dent himself. Here – with no acknowledgement to Englehart’s stories, mind you – Harvey Dent is himself the handsome, blonde, upright politician seeing Batman’s ex, but instead seduced into crime by The Joker.

Stated Steve Englehart himself: “In my version, it’s Two-Face talking to another guy who’s been heavily damaged on the left side, and who is another ‘golden boy’ politician, so it makes sense that Two-Face could convince Evan Gregory. They share a bond. In the film version, it’s the Joker talking to Harvey Dent. Those two have nothing in common, and Dent has hated the Joker the entire movie. It was a storyline in search of a reason to be there.” Englehart went on to point out that he hadn’t continued to flesh out the whole comics story at the time of Nolan’s film, “which is why the last half hour of The Dark Knight feels so tacked on.” But enough about the scarring of Two-Face himself by the filmmakers – there was much more damage done. Many more characters were thrown away or manipulated to suit Nolan’s crime thriller.

Robin was hinted at, without any reference to Dick Grayson, Jason Todd, Tim Drake, or circuses, but instead, here found his roots in nothing less than the corridors of the Gotham Police Department as a flatfoot civil servant. When corporate villain Daggett was introduced, Nolan couldn’t bring himself to make it Roland Daggett in homage to the animated series; it was John Daggett. Out was Officer Montoya; in came Detective Ramirez. Grace Lamont was nowhere to be found; Rachel Dawes was Dent’s love interest.

Yes, the Nolanverse had placed itself over and above anything the mere fan-boys had cherished; he was their new God to worship, and gone were the old ways. It’s almost as though Nolan looked down at the Batman source material patronisingly, and again, it was used more as a way for him to engage in some clever filmmaking. Whereas Burton was the fascinating geek goth telling stories with heart, Nolan was the fuddy-duddy middle class professor being incredibly intelligent but boring you to death with his clinical tales of twists and turns, showing off his supposed cerebral superiority.

In the first follow-up, the Joker was not just a mysterious vagrant and gifted fighter able to match fisticuffs with Batman (a joke in itself), but also an “agent of chaos” who wanted to “introduce a little anarchy.” This unbleached Joker was a blank canvas for America’s fears, bearing only the smears of face paint – or “war paint” as Nolan rationalised – and while supposedly representing the often-peaceful political philosophy of liberty without authoritarianism that is known as anarchism, was considered a “terrorist.” The Joker even stated: “Do I really look like a guy with a plan? You know what I am? I’m a dog chasing cars. I wouldn’t know what to do with one if I caught it! You know, I just do things.” So, the feeling was that there was no rhyme or reason to the Joker’s actions, reflecting the American Bush-era perspective that “terrorists” just do what they do…because. There is, we were told, no point in scratching beneath the surface.

On this basis, throwaway explanations can be something as vacuous as “they hate freedom,” as George W. Bush Jr himself once claimed. His administration’s Patriot Act that attacked civil liberties by spying on their own citizens was introduced on the premise of combating the supposedly constant, elusive, irrational threat of “terrorism” where W. himself said, “When we’re talking about chasing down terrorists, we’re talking about getting a court order before we do so. It’s important for our fellow citizens to understand, when you think Patriot Act, constitutional guarantees are in place when it comes to doing what is necessary to protect our homeland, because we value the Constitution.”

In The Dark Knight, Batman hacked into all the cellular phones in the city to track down “terrorist” Joker, and Lucius Fox told him: “You took my sonar concept and applied it to every phone in the city. With half the city feeding you sonar, you can image all of Gotham. This is wrong,” to which Batman replied, “I’ve gotta find this man, Lucius.” When Fox asked at what cost, Batman made excuses. Andrew Klavan wrote in the Wall Street Journal: “Like W., Batman sometimes has to push the boundaries of civil rights to deal with an emergency.” That this perspective is used in a Batman film, Klavan explains, is because “Hollywood conservatives have to put on a mask in order to speak what they know to be the truth.” This is quite frightening stuff, if a fair summary of Nolan’s work serving his stories through the Batman mask. The eyes are the windows to the soul, and whereas Michael Keaton’s (below) did much of Burton’s storytelling for him, Christian Bale’s were lacking expression, symbolically serving to conceal the soulless nature of Nolan’s miserable version.

But The Dark Knight made even more money: blowing Burton’s Batman away by doubling that film’s takings (though to judge popularity by this, given the changing price of cinema tickets, remains complicated), it was a billion dollar dream for Warner Brothers, who knew they needed Nolan to return one more time to make a third. By this time, it was easier to brace yourself for the nasty little mean-spirited right-wing themes Nolan was plotting, and in the midst of a post-financial crisis United States, polarised by Occupy Wall Street on one hand and the right-wing libertarian Tea Party movement on the other.

The graphic novel Batman: The Killing Joke had inspired Burton’s Batman, of course, and the novel’s writer Alan Moore was more than happy to offer his thoughts on the political unrest in the U.S. and his native U.K.: “At the moment, the demonstrators seem to me to be making clearly moral moves, protesting against the ridiculous state that our banks and corporations and political leaders have brought us to.” However, naturally, Nolan seemed more aligned to the perspective of Batman: Year One and RoboCop writer Frank Miller, who said: “The ‘Occupy’ movement, whether displaying itself on Wall Street or in the streets of Oakland (which has, with unspeakable cowardice, embraced it) is anything but an exercise of our blessed First Amendment. ‘Occupy’ is nothing but a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists, an unruly mob, fed by Woodstock-era nostalgia and putrid false righteousness. These clowns can do nothing but harm America.” Alan Moore, in turn, responded: “(The ‘Occupy’ movement) is a completely justified howl of moral outrage and it seems to be handled in a very intelligent, non-violent way, which is probably another reason why Frank Miller would be less than pleased with it. I’m sure if it had been a bunch of young, sociopathic vigilantes with Batman make-up on their faces, he’d be more in favour of it.”

But Nolan’s franchise kept heading in the direction in which it had begun – which was clearly more “Miller” than “Moore.” In the second sequel, Batman returned from retirement to tackle Bane, who here was not the Latin American muscleman of the comics and cartoons, but a short, chunky, Yoda-voiced “terrorist” from the Middle East merely under the guise of a freedom fighter, kidnapping precious stock exchange suits, bringing Gotham City to its knees and leaving the people to run amok. Then there’s cat burglar Selina Kyle (but not “Catwoman,” a term too unrealistic for Nolan, we can assume): unlike with Batman Returns, where Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman stopped being in service or submission to men, Selina Kyle here, alongside Miranda Tate, often acted in both. While the film had promise when she told billionaire Bruce Wayne, “You’re all gonna wonder how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us,” she then lured Batman into the grip of Bane, who imprisoned him in a Middle Eastern cell, and left him to watch as he trapped the entire Gotham police force before revealing his true motive: simply destroying the entire city.

Again, the rebel (and his revolutionaries) represented simple “terrorists” with no method to their madness, and the scenes depicting riots and looting of mansions, followed by kangaroo court show trials, played out like a parody, ridiculing the very concept of uprisings and categorising them all as evil, comparable to the Reign of Terror or the Great Purge at their worst. The fact that Bane not only sought to wipe out an entire city, but aimed to do so with a green energy device that was instead co-opted as an A-bomb, only reinforces the cynical, right-wing perspective of Nolan’s films. As Catherine Shoard wrote in The Guardian: “The Dark Knight Rises is a quite audaciously capitalist vision, radically conservative, radically vigilante, that advances a serious, stirring proposal that the wish-fulfilment of the wealthy is to be championed if they say they want to do good. Mitt Romney will be thrilled. What’s strange is that quite so many of the rest of us seem to want to buy into it.”

When Gotham’s police force are trapped underground, we’re told that they’re “not just people down there, they’re cops,” leading to a showdown in the streets between the officers on one hand and the revolting rioters on the other, again reinforcing the binary black-and-white view Nolan supposedly blurred in his first two attempts, all the while tarnishing Batman rather than redeeming his enemies in the process. Once more, the message to moviegoers and their children was to trust power, even if it means sacrificing freedoms, because those who wish to question authority under the banner of making the world a better place are, in fact, themselves not to be trusted; they have a hidden agenda – the “ugly” face of socialism that will, we’re told, lead us to death and destruction. Author David Sirota wrote at Salon.com: “When villainous motives and psychopathy is televisually ascribed to mass popular outrage against the economic status quo, it suggests to the audience that only crazy people would sympathize with such outrage.” He added: “Knowing the teenage audience is right now forming the next generation’s vision of good and bad, it’s a message that the 1 percent must love.”

And, as the movie almost equalled its predecessor, they did love it. Whereas The Dark Knight was provocative enough to leave room for at least a little debate about its themes and questions raised, the American right-wing wholeheartedly embraced The Dark Knight Rises, as is understandable. “The entire film is an ode to traditional capitalism,” claimed right-wing commentator Ben Shapiro. “Furthermore, while we learn that Bane spent time in poverty in a prison – and that it toughened him up – Bruce Wayne can get just as tough, though he grew up with tremendous wealth.” He went on to point out the movie’s endorsement of firearms: “At one point, (Selina) Kyle has to save him by using guns – and she tells him that she disagrees with his rule. It’s hard for the audience to disagree, seeing as all the bad guys have guns – and in one scene in which thousands of cops charge the Occupy Army of Bane, the Occupy Army blows the underarmed cops away.” Andrew O’Hehir, over at Salon.com, explained: “It’s no exaggeration to say that the ‘Dark Knight’ universe is fascistic, and I’m not name-calling or claiming that Nolan has Nazi sympathies…It’s simply a fact.” He called the film “an unfriendly masterpiece that shows you only a little circle of daylight, way up there at the top of our collective prison shaft.” Everyone across the spectrum was in agreement: the so-called Nolanverse was fascistic.

Yes, the Tea Party movement, Paul Ryan, and Mitt Romney must love it. There were few shades of grey here, as we had with Burton or the subsequent animated series. This has been the killing of Batman as a vulnerable, tragic, disturbed figure fighting for the oppressed and exposing the corrupt at his best, and beating up petty crooks at his worst, his major foils all born out of often equal tragedy and, through circumstances, taking different paths in life – the stories, left untold by Nolan, of Mister Freeze, whose wife was left to perish after his cryogenic freezing chamber was discontinued by the greedy corporation funding his research; of Clayface, whose acting career and celebrity depended on superficialities of appearance and whose very stage makeup consumed him; of Killer Croc, whose medical condition left him deformed, cast out by his family, leaving him residing in the sewers; all with questions the Riddler himself would be proud of: what separates these villains from vigilantes, or the police from politicians, or governments from corporations? Understanding psychological trauma and social conditions may provide some answers, but Nolan was more interested in absolute good, and pure evil.

The final film in Nolan’s Batman series has, of course, been often overshadowed by the shooting at an Aurora, Colorado, movie theatre that left 12 people killed and 58 injured at the hands of a seemingly Nolan-obsessed killer who said, “The message is: there is no message,” at a time when death threats were being sent to those of us who dared to criticise this latest offering. With such a dark view as Nolan’s, championing the individual and the right to bear arms, while demonising villains as one-dimensional terrorists who hate the freedoms we ourselves must be prepared to sacrifice for our rich and powerful patriarchal masters, this all seemed a tragic yet logical conclusion to the franchise. As Batman costumes were being banned in the subsequent hysteria, were Nolan’s people suggesting it’s a sacrifice we must accept as worth making? After all, we are led to assume that all killers are evil, and all rebels are wrong.

A wise man once said, “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.” As mentioned, Tim Burton’s mistake has been to move on from the Batman films without political awareness. But Christopher Nolan produced his series unashamedly ignorant of the terrible themes and messages he was creating, and the filmmaker, like Clayface, has been consumed by the ugly makeup of his very own aesthetic. “The films genuinely aren’t intended to be political,” he said. When countered with the claim that all art is political, Nolan replied, “But what’s political?” As the Skunk Anansie lead singer Skin sang, “Everything’s political.”

Until these movies are directed by a filmmaker who recognises that – and the power and responsibility that this medium inherently affords – Batman will remain killed off. For now, like our hero, we fight on through the loss; we still have many, many comics and animated episodes in which to take solace before redemption is to be found in Hollywood.