Batman: Making a Killing (part one)

Batman has a dark soul. Whether that’s used for good or not is in the hands of the beholder.

What comic book character has been so enduringly popular as Batman for the last 70 years? After Superman, you’re hard pushed to think of one that comes even close – in almost every major ranking, Batman is right there, second only to “The Man of Steel” himself.

Superman came about at a time of political extremes and talk of races of supermen, to become a symbol of Rooseveltian American freedom and refuge to others’ poor and persecuted, and while he would go on to, in fact, become a posterboy for blind patriotism, Batman always remained in far more interesting territory.

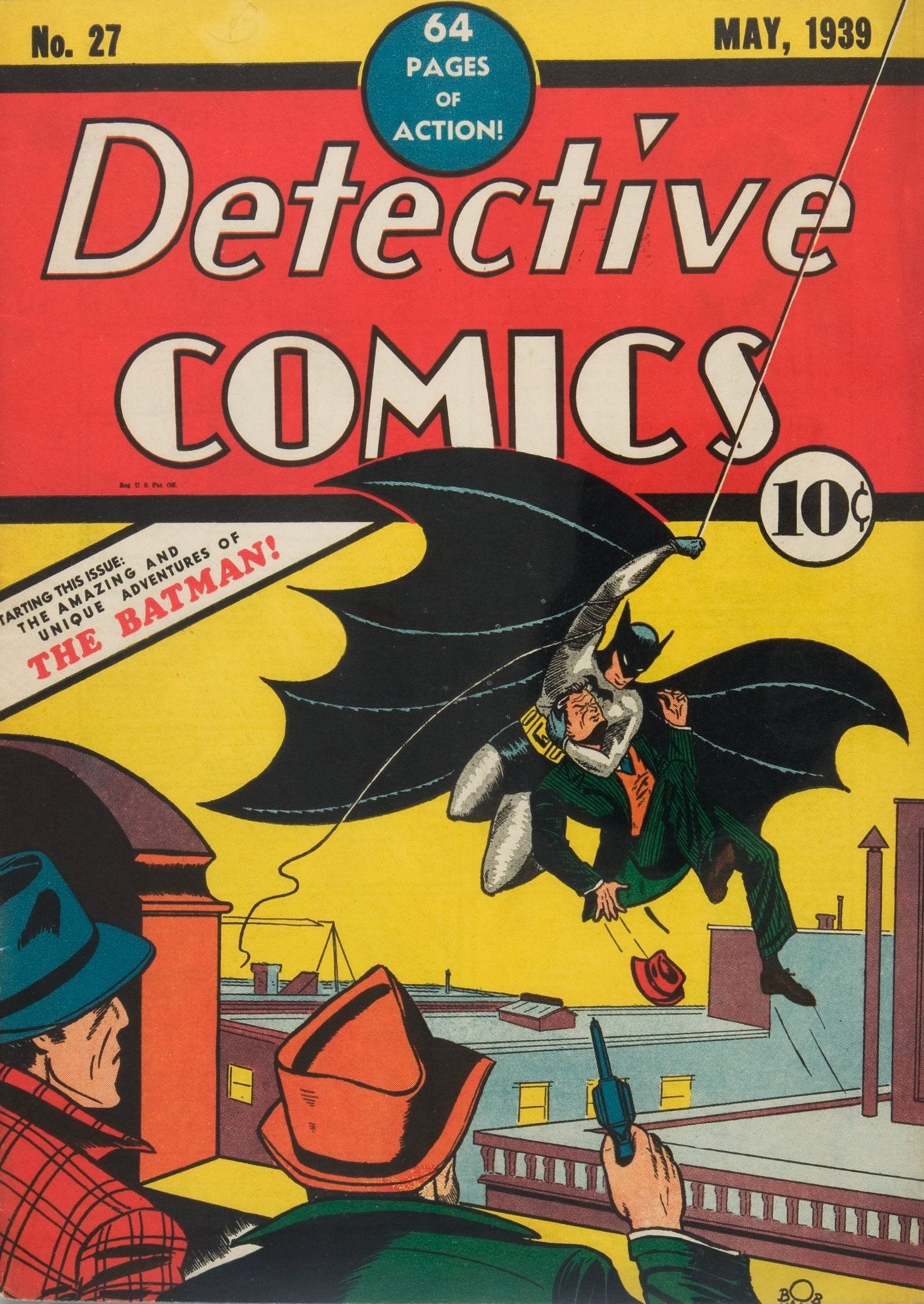

Inspired by Leonardo Da Vinci flying machine designs, comic strips and pulp fiction books from The Phantom to The Shadow, as well as Zorro and the film Bat Whispers – where a criminal in a cape shines a bat signal before committing murder – Bob Kane developed a crime-fighting vigilante “Caped Crusader” who would, one year after Superman’s debut, follow him into the annals of pop culture history. Batman frequently joined Superman in 1940s comic books to fight against the evils of the Axis powers of the Second World War.

With such anti-fascist sentiment, of course, the 1950s saw a backlash in the United States as Soviet Russia threatened their superpower status, with Hollywood subjected to witch-hunts from Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee, and even comic books targeted as a dangerous threat to wholesome apple pie-American family values and consumerism, and the Comics Code Authority was formed to monitor the comic book medium in the midst of outlandish claims that the relationship between Batman and Robin was – shock, horror – perhaps not strictly heterosexual (for those who feel the need to know, it actually was).

But the irony is, that as a result of all this and the subsequent changes made to the aesthetic, you could be forgiven for having thought differently, as the camp 1960s television show starring Adam West as Batman and Burt Ward as Robin had the Bat and his sidekick donning tights, skipping along, and fighting crooks in broad daylight, with crayola colours, bad jokes, and a swinging sixties “Batusi” go-go style dance. It was vacuous; it was awful.

After the 1978 success of Superman as a comic-to-screen adaptation, Hollywood realised that Batman could perhaps translate to the cinema medium, too. However, when Superman’s writer, Tom Mankiewicz, drafted a screenplay for a Batman movie, it was almost as lighthearted as the series.

Producers Jon Peters and Peter Guber enlisted relatively unknown Tim Burton for directorial duties after he’d made cult hit Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure and box office success Beetlejuice, and the choice took the project into a darker direction. Despite growing up in hot, sunny, Burbank, California, watching the television show, the pallid, black-robed Burton preferred the evolution of the comics in the 70’s and 80’s that focused further on the trauma that made millionaire Bruce Wayne become vigilante Batman. “It’s a guy dressing up as a bat and no matter what anyone says, that’s weird,” said Burton.

"The rich. You know why they're so odd? Because they can afford to be." - Alexander Knox, in Batman (1989)

With Hollywood speculating that the likes of Mel Gibson and even Sylvester Stallone might be cast to play the lead in Burton’s Batman, the director instead selected his Beetlejuice friend Michael Keaton, a relatively unthreatening yet versatile actor who was hardly A-list, provoking a huge backlash from fans whose complaints even made the pages of the Wall Street Journal. “It would have been very easy to go for a square-jawed hulk,” reasoned Burton, “but if some guy is well over six-feet-tall with gigantic muscles, what’s the point in him wearing armour with an arsenal of weapons and gadgets?” Developing a story about a rich, reclusive loner obsessed with avenging the murder of his parents, Burton while producing the picture put together rushed trailers of footage to be screened at movie theatres everywhere – and when they witnessed Keaton whispering “I’m Batman” in a gravelly voice, by God, they believed him. While the costumed Keaton modestly joked that he felt like Elvis in the Vegas years, film crew members were in awe by his transformation once in the suit. He was completely different as the shy, retiring Bruce Wayne, compared to his portrayal as Batman, acting through the mask with his eyes, dialogue kept to a minimum to retain mystery, simmering with subdued rage.

Burton had used Alan Moore’s graphic novel The Killing Joke as inspiration for the film’s feel, and after sharing it with Jack Nicholson, successfully convinced the actor to play the Joker, written here as a mobster set up by his boss for having an affair with his moll, dropped into a vat of chemicals that left his skin bleached white and his mind unhinged, a pivotal plot device that brought about everything after it, and even called into question the ramifications of the sometimes-fascistic vigilantism of Batman. Nicholson scored one of the most lucrative film deals ever, making money off the film and its franchise to this day.

With incredible Pinewood Studios sets of an oppressive, gothic, gargoyled Gotham City “as if hell had erupted through the pavements and kept growing” and a sleek Batmobile symbolising sex and violence, all designed by Anton Furst, in addition to a Baroque operatic score by composer Danny Elfman, the film noir homage was a killer, and became a massive box office hit, making over $400 million. It was also for the most part an artistic and critical success, redefining the comic book genre completely following the Superman adaptations, and justifying daring casting decisions in the industry. Its impact on film is too often understated – The Crow, Spider-Man, X-Men, Avengers, and even V For Vendetta would never have been treated as serious proposals without 1989’s Batman.

Though some thought the film was “too dark,” Burton himself found such claims disturbing considering the cynical cops-and-guns movies that were released at the same time, bringing into question the definition itself. “They see people walking around in regular clothes shooting guns, and it makes them feel more comfortable than when people are dressed up in weird costumes,” said Burton. “I’m disturbed by the reality of that; I find it darker when there’s a light-hearted attitude to violence and it’s more identifiable than when something is completely removed from reality. I’ve always had trouble understanding that.”

Gaining overnight creative clout and freedom to deal further with interesting, tortured characters, the visionary Burton cast then-unknown Johnny Depp as the lead in Edward Scissorhands, about a boy with scissors instead of hands that are paradoxically both creative and destructive – the film based on sketches by Burton as a child in Burbank, dealing with issues of acceptance, judgement, and depicting the uniformity of suburban life as sinister. With Burton succeeding in Hollywood, Warner Brothers had to give him carte blanche if they wanted him to direct a follow-up to Batman. And they did.

"A man dressed as a bat is a he-man, but a woman dressed as a cat is a she-devil. I'm just living down to my expectations." - Catwoman, in Batman Returns (1992)

Having lost his friend Furst, who had thrown himself from a rooftop to his death following Batman, for the follow-up Burton made sure to surround himself with others who he could depend on. In addition to the returning Elfman, he brought in production designer Bo Welch, cinematographer Stefan Czapsky, and producer Denise Di Novi amongst others, all of them back-up from Edward Scissorhands, and had Heathers writer Daniel Waters define the Catwoman character as the bullied, dowdy secretary turned kick-ass feminist portrayed by Michelle Pfeiffer, while actually adding layers to the previously fat yet flat Penguin persona, developed into a well-rounded three-dimensional former circus freak abandoned by his wealthy parents. Danny DeVito played the Penguin, staying in character throughout production. The film also touched on patriarchal oppression, with Catwoman’s former boss Max Shrek (named after Nosferatu actor Max Schreck) developing a power plant that would, in fact, not generate power for Gotham, but steal and store it – symbolic of Burton’s cynicism towards corporate power at the time. Despite this, the film is careful to make every character sympathetic in some way, presenting redeeming features and even explanations for their atrocities.

While Batman was impressive, Batman Returns was stunningly beautiful, often shot with a wintery blue tint and entirely inside an elaborate, deliberately crowded Warner Brothers studio that Pfeiffer herself at one point got lost in, with its temperature dropped to subzero for the lead villain’s live penguins and for visible breaths in the air; crew members stepped from sets full of real snow and ice out into sunny Californian streets, still wearing their parkas. Abandoning the cartoon animation from the first film and adopting then-groundbreaking computer techniques, the movie may be now more than a quarter of a century old but looks like it could have been made last year, due in part to the timelessness of the overall design that paid homage to the 1940s and 50s emergence of the Batman character, while incorporating styles from numerous eras. Fascist city sculptures and pavements-built-upon-pavements further exacerbated the feeling of claustrophobic urban landscape, incomplete development, and oppressive regimes, while Batman’s own appearance and armour design became more art deco. The film like no other exposes Burton’s influences rooted in German expressionism: in addition to Nosferatu, in Batman Returns it’s easy to see the likes of Metropolis and Cabinet of Dr Caligari in the aesthetic.

Though grossing well over $250 million at the box office in 1992, the huge profits were no match for Batman and not enough for wanting-more Warners, who were uneasy with the more Burtonesque film, with its baby-snatching plot elements and its sadomasochistic subtexts. The Happy Meals™ and toys were becoming more difficult to market to children without backlash from conservatives, and Warners were unnerved. Burton dismissed the concerns: “I think children have their own barometers,” he said. “I was always grateful for heavier subject matter when I was growing up.”

Ultimately, though, the notorious knee-jerk prompted by the studio system’s greed led to a mistake that would, in the long-term, cost them millions: with more material left to enjoy, they decided not to bring Burton back for a third film, and at the time, any attempt to publicly express a firm belief that the franchise was going to head for disaster was dismissed. But having already inspired what is largely considered the best animated series of all time that featured an Elfman theme and Burton motifs all over it, the style was going to be difficult to depart from. While the comics were enjoying some of their juiciest stories ever, and all subsequent comic book movies were influenced by the ground broken by Burton, Batman: The Animated Series finally superseded the live-action serial of the 60’s, and Batman in the popular consciousness was almost entirely based on this “dark deco” interpretation. In turn, the show continued developing characters in that vein – Two-Face, the unstable District Attorney with a tortured soul who has half his face scarred by acid that literally and figuratively exposes his dark side, was presented as the third villain in line to the throne of the rogues gallery, and beautifully Burtonesque in his split suit of black and white and torn, dark complexity. His brooding presence in a third Burton movie was highly anticipated, but it was not to be.

Appeasing Burton by giving him a token producer credit on the third film, Warners brought in Joel Schumacher at the helm. At first, this seemed like a great choice: Schumacher was responsible for the deliciously dark The Lost Boys, Flatliners, and even the controversial yet thought-provoking Falling Down. There was little doubt he could do justice to the material at his disposal. But Warners were clear that he must create something lighter than Batman Returns, lighter than Batman, and even lighter than Flatliners and The Lost Boys. Having read the script, Keaton rejected the offer to don cape and cowl again, and Schumacher cast the younger, more male-model Val Kilmer to replace him. While still exploiting what was widely accepted as the Batman signature theme by Elfman, the first trailer for the third film in 1995 showed Kilmer sporting rubber nipples on the batsuit, alongside the wasted talent of Tommy Lee Jones screaming, shouting and gesticulating wildly as the normally dark and moody Two-Face, in addition to Jim Carrey’s Riddler – whose mind-reading device in the story seemed like something Mad Hatter would create in the comics. Schumacher utilised a high-tech, high-rise Asia-inspired cityscape and his trademark neon lighting and glow-in-the-dark paint palette for the film, which finally introduced Robin while Batman went through the film over-articulating his over-wrought self-perception rather than simmering in the darkness. Meanwhile, Carrey even based his portrayal of the Riddler on that of Frank Gorshin’s own in the campy 60’s show, and this was representative of the whole regressive nature of the franchise by this time. The wheels of progress towards interesting territory were ground to a halt, and put into reverse by the studio.

Generating over $335 million at the box office, it was more than Batman Returns but less than Batman – though this didn’t seem to matter to Warners because of the large range of merchandising opportunities this lighter, brighter version opened up for them. The film’s title, Batman Forever, suggested Warners were confident they could keep going back to the well an infinite number of times, banking on families with money to spend and enough ignorance or indifference to the source material to care about the sacrilegious bastardisation of the Batman characters. The franchise had to go on – because the bank account, not the material, required it; sequels planned through greed and nothing more. Tolkien, this was not.

But Warners were so sure of themselves, they actually thought they were headed in the right direction, moving up and away from what they saw as the dark depths of the “mere” $250 million from their 1992 Batman returns. So, when Schumacher fell out – as all directors seem to – with Kilmer, and George Clooney was cast as Bruce Wayne and his alter ego, Clooney’s colleague Uma Thurman arrived on set and was forced to do take after take after take to sufficiently ham up her performance as Poison Ivy. Thurman had seen Pfeiffer’s Catwoman, and was sorely mistaken in believing she ought to aim for a similarly sophisticated performance. With Arnold Schwarzenegger playing Mister Freeze as though he were Rainier Wolfcastle as McBain in The Simpsons, and Jeep Swenson as a Bane reduced to a grunting henchman, this fourth film was uncomfortable, even downright embarrassing, to watch. “There was a lot of pressure from Warner Brothers to make (the film) more family-friendly,” explained Schumacher at the time.

The direction was wrong for Warners, whose avarice had made them push their luck too far, and 1997’s Batman and Robin failed to reach Batman Returns levels of box office success, while also being universally slated – one critic saying “Schumacher’s tongue-in-cheek attitude hits an unbearable limit,” and even star Clooney – who under a different direction could have perhaps been truly great as Batman – admitted that on reflection the film was a waste of money. This was a version of Batman killing the franchise. The widespread disgust became so overwhelming that finally Schumacher himself had to offer an apology to audiences: “If I’ve disappointed them in any way, then I really want to apologise. Because it wasn’t my intention. My intention was just to entertain them.” But it wasn’t really Schumacher’s fault. It was Warner’s petulant greed and impatience taken to its inevitable conclusion.

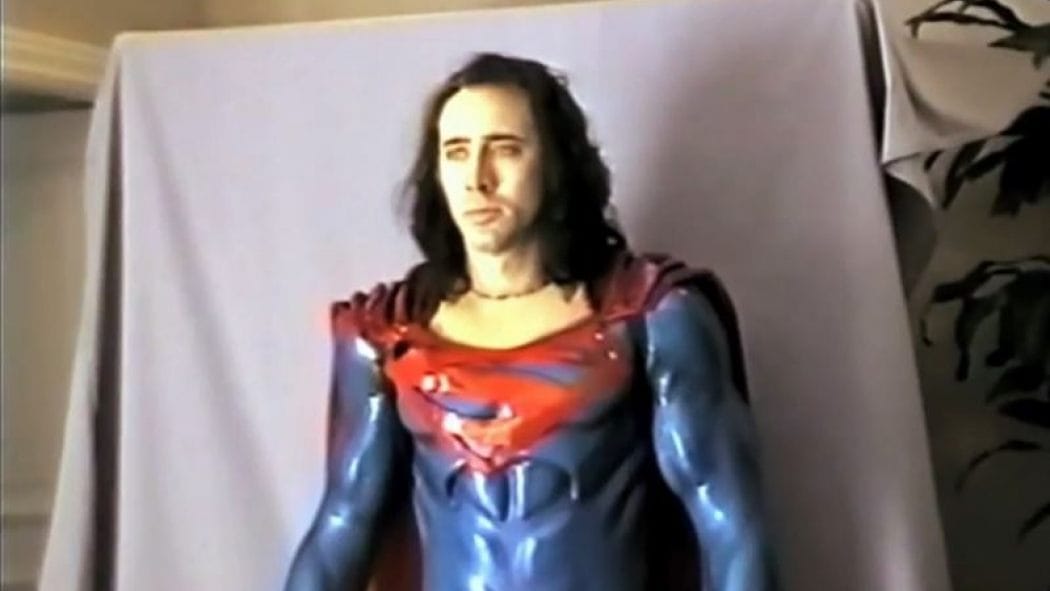

With Burton proven right, he was courted by Warners the following year to instead turn to Superman, hoping he could adapt the character for contemporary audiences in the same way he had with Batman. He’d even proved he could lighten up, by directing Mars Attacks!, the 1950s style sci-fi comedy that was based on trading cards of the same name and which exorcised all of Burton’s rage at American culture, amusing British audiences but angering American patriots. Interested in focusing on and playing up Superman’s status as an alien adapting to human life while being secretly and inherently different from everyone else on the planet, Burton scrapped the gaudy red, blue and yellow spandex in favour of an electric suit, and understandably rejected Superman’s chances of hiding his identity completely by simply wearing a pair of spectacles, instead casting the sometimes-brilliant Nicolas Cage and agreeing with him that the actor would have to use his physical acting ability to hide Clark Kent’s true identity from other humans.

Comic book fan and Dogma director Kevin Smith wrote a screenplay that read more like the fantasies of a Superman geek-boy, full of insider references, prompting Burton to scrap it, and provoking an immature response from an otherwise smart Smith, who has publicly and pathetically attacked Burton ever since in one of the worst cases of sour grapes in movie history. When Burton suggested he himself never read comic books as a kid, Smith quipped, “that explains Batman” – despite the fact that the entire comic book film genre as we know it today would not exist without Burton’s influence.

But beyond Smith, the wider backlash to Burton’s updating of the costume and casting of Cage proved even greater than that in response to his choice of Keaton a decade earlier. With $30 million already spent in development hell, Warners put the whole franchise on hold and relieved Burton of his Superman duties. At the time of writing, it’s still yet to see a decent movie. Burton went on to direct the wonderfully creepy Sleepy Hollow, the off-target Planet of the Apes, and the quirky tear-jerker Big Fish, all of which began his consistent approach of preferring existing material that he could translate in his own way that coincided with his romantic relationship with Helena Bonham-Carter. And so followed Charlie & the Chocolate Factory, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, Alice in Wonderland, and Dark Shadows, all starring Bonham-Carter, laden with CGI from the one-time proponent of stop-motion animation, and lacking in political awareness (just look at the Chocolate Factory’s Oompa-Loompas, “African pygmies” all universally played by the same short-statured Kenyan actor). Moving to the more suitably dreary London, England, at a time when the country was about to go full-on Victorian Era, run by David Cameron’s most right-wing British government since the Second World War, Burton’s political ignorance would only be reinforced by Bonham-Carter’s claim that Cameron, a close friend of hers, is “not a right-wing person.” All while he was busy scrapping the UK Film Council, clamping down on the internet, selling off the state, and wiping out communities to pay for the debts of his banker buddies.

By then, enough years had passed for Warners to dare revive the Batman brand to plumb for profits. Burton had long since moved on, and the studio began instead looking to other talented directors to reboot the franchise. Wolfgang Petersen and Darren Aronofsky were both under consideration, at various times. But it would be Christopher Nolan to bag the job. And while Schumacher’s involvement might have represented the killing of Batman artistically and commercially, Nolan’s would do something much more sinister: it would kill Batman’s very soul.

Find out why in part two next week, featuring Alan Moore, Frank Miller, the Occupy movement, the Colorado shootings, the stench of fascism, and more!